OPINION: HBO's 'The Hype' Reminds Us That Black Women Deserve More

Photograph by Tobin Yelland/HBO Max.

From my couch, ironically in an oversized CNK Sweatshirt, I shouted “YOU ELIMINATED PAIJE!?!”

I’m referring to Paije Speights (pronounced “Paige”), the Detroit-based designer who captured our hearts and cosign in just eight episodes of HBO’s The Hype which, if you’re unfamiliar, is like Project Runway but the streetwear version. If you've yet to see HBO's The Hype, you may want to catch up before you read. The Hype is a design competition where nine of the country’s most promising young streetwear designers compete each week to get the “co-sign” from a guest artist as well as the show’s three judges. The judges — or “co-signers” — are rap superstar Offset, Emmy-winning costume designer and stylist Marni Senofonte, and Bephie Birkett, who co-owns streetwear megastore Union. The winner of the eight-episode season gets the title, mentorship, and a grand prize of $150,000.

With her oft underestimated hustle and a feminine take on streetwear that would match perfectly with every bamboo earring we own, Paije easily became one of the contestants we were not-so-silently rooting for. For many of us, the ladies of this competition (including contestant Camila Romero and early castoff Murph) represent that delicate balance we straddle in a streetwear industry dominated by and catered to men. For those of us who have spent years crafting looks from oversized fits and smaller sized men’s garments, Paije and the evolution of her The Hype journey brought forth the tantalizing possibility of not only another woman-led streetwear brand but a streetwear brand crafted by a Black woman who understands our bodies, our curves, and the erased legacy of Black streetwear Queens.

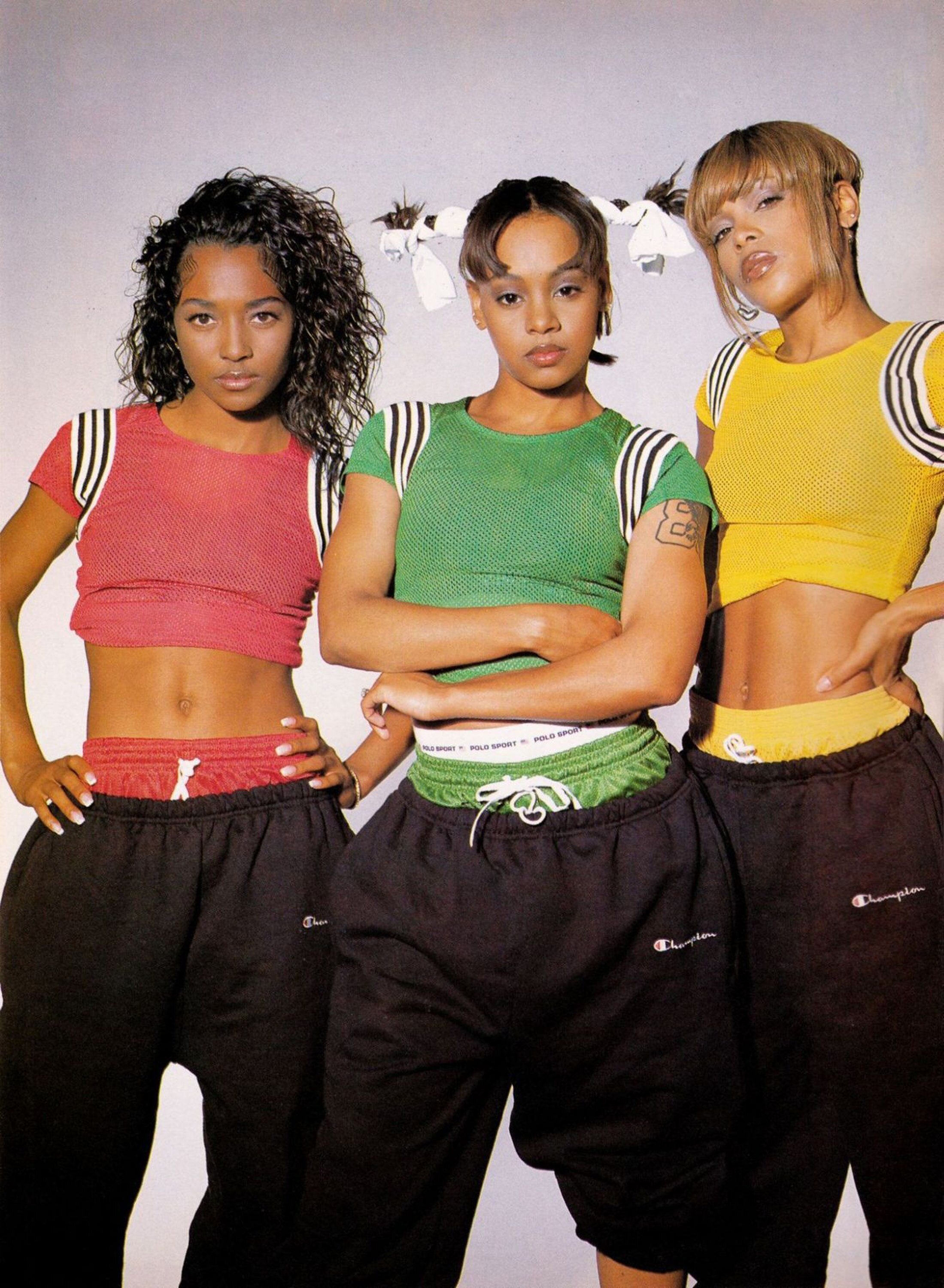

It's easy to get swept up in the allure of what streetwear has largely become: high-priced jackets and designer tees, but at its origins, streetwear was style born out of necessity and generational evolution in Black and Brown communities. Now, visual campaigns from prominient streetwear houses find us inundated by imagery of the commercially viable female sneakerhead: racially ambiguous or white, with a model physique. It's rare to see a representation of the Black women we stood in line with outside of Footlocker, better yet, we rarely see a representation of the Black women who raised us. You'd almost forget that Black women like April Walker, Misa Hylton, Mary J. Blige, SWV, Aaliyah, TLC, and Missy Elliott were some of the trailblazers of the culture who made wearing oversize fits, sneakers, fitteds, and door knockers a staple for 90s girls. Frankly, there would be no streetwear as we know it without the trendsetting influence of these women and others like them.

For The Hype the authenticity of the confessional is often inconsistent with the actual decision-making. While the show separates itself from the slew of DIY reality TV as a program that pushes the culture forward, designers who are “at the forefront” are sent home—the boundary-pushing clothes, alas, are at odds with market trends and the key partnership with StockX, where winning designs are duplicated and sold. Even towards the end, the message of social change and addressing racism isn’t profitable — or, in the words or cosigner Offset, “low fashion.” This strained relationship between authenticity and profit makes The Hype’s DIY ethos feel decorative but, what can you really expect from a show nicknamed after one of the more controversial terms in our space? Hello, HYPEBEAST.

That’s what makes The Hype, and ultimately, the results of Paije’s last few challenges, a hard thing to reconcile. From Episode 1, Paije was very clear about her mission: rep Detroit, rep the ladies, and rep Black people. In each challenge, in everything from her choice in model to her actual design, there was always a story rooted in the elevation of the Black community and putting a spin on style elements that originated in our spaces. From a du-rag “cape” for a “Black Harley Quinn” in a DC Comics challenge to illustrating the importance of Sunday chuuuuch in the Black community by crafting a beanie “church hat” that I’m pretty sure my own grandmother would wear, Paije hit her stride by telling our stories through garments and giving us a glimpse at a brand that could speak to our experiences, even when those experiences led to uncomfortable conversations.

“Black designers don’t get as much credit for being innovative as we should. It’s almost a slap in the face when you see someone taking credit for stuff that started in your community a long time ago so, I feel like by putting this on the back of my jacket, it sends a statement.”

Throughout Season 1, we saw all of the designers navigate a space that forced them to grow and level up. But, we also saw a different element of the struggle for Paije that many of us can relate to. For Black women, the experience of being underappreciated or undervalued despite being asked to take on more work is hardly an exclusive experience. As viewers, we witnessed Paije extending herself to fellow designers Camila and Alan who, truthfully, didn’t have the expertise necessary to tackle their tasks. We also watched as Paije struggled after the killing of 15-year old Ma'Khia Bryant by police in Ohio and reiterated what we all felt in those moments earlier this year:

“I’m a little irritated today. Just tired of going on the internet and seeing Black people being killed. I feel like yesterday we have a whole little victory [after the Derek Chauvin verdict] and not even hours later you go on the internet and see a 15-year-old girl being murdered. It’s just tiring. My son is a Black boy who will eventually one day be a Black man in this country and it’s scary. You’re teaching your kids all the right things to protect themselves but what happens when the person you go to for protection is the person that harms you? How do you teach that?” Paije channeled that emotion into a garment that would land her first challenge win.

Yet, there were still moments when we saw glimpses of what Black women in streetwear could really accomplish together. The moments where we saw mentor Bephie meeting with Paije and then singing her praises in a confessional is a moment that struck us as so necessary. To see a strong Black woman who has made a name for herself in this streetwear game going out of her way to provide a young Black designer with invaluable insights is the “each one, teach one” ethos in action, and, resulted in a Paije design we’d buy right now.

Photograph by Danielle Levitt/HBO Max

“Black women, our fashions and the things that we’ve made, have influenced so many people and we’ve never gotten credit for it. Paije being here is shining a light on the part that we play in fashion and the part that we play in streetwear.”

- Bephie Birkett, The Hype Episode 7

Yet, as much as we rock with Bephie, her words often didn’t match the decision-making we saw displayed amongst the cosigner panel and, as Paije was eliminated after a lookbook showing that was not only cohesive but, incredibly technical AND evolving in favor of two designers who — from our perspective — didn’t evolve in their original aesthetics nearly as much. For us, Paije deserved more and so did Black women.

“I really feel like I’ve been completely blindsided. But, the fact that I didn’t win is ok. Because I had a bigger purpose here than winning. I got my message across, my social statement across, and to talk about things that I don’t feel are talked about enough. It’s only up from here for me.”

In the end, The Hype offered no women finalist and no Black finalist in a competition based on the very culture it claims to respect. Where is the diversity? Of the 3 co-signers, two are women, and two of them are people of color, yet, they perpetuated the status quo. While the contestants were all talented and the idea of the "best person" winning is incredibly subjective and rightfully up for debate, what isn’t is the message The Hype sends to young girls and specifically Black female designers: you can work twice as hard, do twice as well and still walk away with half as much. Black women, the originators of much of this culture we covet, deserve better.